In 2013 I wrote a blog post titled “The Four Types of Innovation and the Strategic Choices Each One Represents.” To date it’s been one of the most popular articles I’ve ever written.

In my original post, I listed the following:

- Breakthrough

- Sustaining

- New Market

- Disruptive

In this post I want to clarify what I mean by each and change the name of the first from breakthrough to Integrative. I’ll explain why below.

FREE VIDEO TRAINING FOR INNOVATORS

Over 100 Slides Free and Downloadable as a PDF

But first, we need to establish some agreement on the definition of innovation itself.

The Definition of Innovation

There are a lot of definitions, so many that it’s been difficult to have a meaningful conversation around the word itself. That said, I subscribe to this definition that I heard first-hand in 2011 from Kenneth P. Morse of MIT:

“Innovation is invention plus commercialization” – Kenneth Morse, MIT

He also adds the following insight:

“It usually takes an entrepreneur, working with the inventor, to bring novel technology from the cool comfort of the laboratory to the cruel crucible of the marketplace.” – Kenneth Morse

If you haven’t seen his lecture on it, I highly recommend watching it here.

While Kenneth’s remarks came from an entrepreneurship angle, the definition still holds if you are in a big company with new technology that you have been tasked to commercialize.

With Kenneth’s definition in mind, another way to frame what he said is to think of innovation as happening at the intersection of a market, new technology and a sustainable business model. The image below illustrates this idea.

This means that for innovation to happen you need three things:

- A market with a need for a solution

- A technology that could enable the solution to be made

- A business model that can create, support, deliver and sustain delivery of the solution to the market

In other words…Invention + Commercialization.

What Is Different About This List?

Several years ago as a new product manager, I needed a systematic approach to innovation within a large company. I was well versed in Clayton Christensen’s theory of disruptive innovation, value chain evolution and jobs to be done. But despite that training, I still felt like major areas were not clear or without sufficient explanation. The theory of disruptive innovation was describing very well one piece of my experience but important parts were still missing with the theory. Aside for most of Christensen’s work, I felt like most innovation theories were confusing and out-of-touch with reality.

For example, I read a lot of articles on “types of innovation” and found a wild assortment of ideas on this exact topic. If you Google “Types of Innovation” you’ll get a lot of responses – all of which seem to claim to be the authoritative list of types.

Larry Keeley wrote a book titled “Ten Types of Innovation” and listed things like “profit model,” “channel,” “process,” etc. All of which are legitimate points if your definition of innovation is broader than what Morse described.

The OECD outlined four types of innovation as “Product,” “Process,” “Marketing,” and “Organizational.” Which is another list that is valid with a broader definition of innovation than what Morse described.

Greg Satell created his own version of the four types of innovation and his list consists of “Basic Research,” “Sustaining,” “Disruptive,” and “Breakthrough.” This list is very similar to the list I created in October of 2013. I was not aware of Greg’s work when I made mine (his HBR article was written in 2017) but the only meaningful difference was his inclusion of “Basic Research.” I don’t include basic research because it falls outside Morse’s definition of innovation as well.

Even Clayton Christensen himself created what he called three categories of innovation including “Performance Improving,” “Efficiency,” and “Market Creating” innovations in an article titled The Capitalists Dilemma. The unusual part about this list is while “Performance Improving” is basically synonymous with “Sustaining,” the other two, “Efficiency” and “Market Creating” are two sides of the same type – disruptive.

I could show lots of other examples of “types of innovation” that people have come up with but I think you get the idea.

This leads me to the broader point, in this article, the four types of innovation that I describe will each fall into the overall definition of invention plus commercialization and they are framed in terms of a specific type of value proposition for each.

Which brings me to my next point…

Innovations Can Be Described Using Economics And Basic Value Propositions

In this list of innovation types, I focus on fundamental economics and value propositions. Markets are still best described by economics on a macro level, and the success of certain products and services are best described by economic value propositions on a micro level.

These value propositions can be simplified down to this equation: This equation says that whenever someone has a need, they evaluate ways of filling that need by taking the benefits of a solution, less the cost and determine which option they believe will bring them the most net value.

This equation says that whenever someone has a need, they evaluate ways of filling that need by taking the benefits of a solution, less the cost and determine which option they believe will bring them the most net value.

If the value proposition is highly relevant to the consumer who hears the message and they agree with the message, they will likely choose to purchase that solution. Over the long run, the product or service that offers the most net value to consumers will most likely win. Each piece of the equation can be described as follows:

Benefits – any tangible, emotional or perceived gain arising from the use of a product or service.

Costs – any tangible, emotional or perceived losses incurred from the use of a product or service.

Net value – the positive or negative net result of a consumer’s evaluation of the utility of a product or service in their life.

For new innovations and value propositions to succeed they must be viewed in comparison to other value props and be seen as the value proposition with the most net value to the consumer.

Below is an example of what most consumers face everyday when considering meeting a specific need.

In order to be innovative, you must achieve a dramatic and positive change to the net value, or bottom line, of a value proposition. To effect a dramatic positive change to net value (to the consumer), you must either dramatically increase benefits of the value proposition or dramatically decrease costs. Some innovation opportunities may even allow you to both dramatically increase benefits, and dramatically reduce costs at the same time – typically this only happens when a new technology comes along.

With this as the background, let’s dive into my updated four types of innovation.

Four Types of Innovation

In general, I categorize innovation into one of the following:

- Sustaining (iPhone 7 to iPhone 8, Gen 2 to Gen 3, etc.)

- Disruptive (Netflix, Chromebooks, Mini Steel Mills, etc.)

- New Market (Arm and Hammer Baking Soda)

- Integrative (the first Apple iPhone, Tesla Model S, Nest Thermostat, etc.)

Innovation Type 1: Sustaining Innovations – Keep The Lights On By Keeping Existing Customers Happy

Sustaining innovation is arguably the most common type of innovation in capitalist, market economies. A sustaining innovation is defined as an incremental improvement to an existing solution that further satisfies existing customers.

The images below illustrate the path of a sustaining innovation relative to the distribution of needs in a market. Clayton Christensen developed this model and explained it very well. In general, people with a need for a job to be done form a market. Among those people in a market are segments of users with needs ranging from sophisticated to basic. The people with sophisticated needs for that job to be done are willing to pay a higher price for a high performance solution.

For example, there is a global market for smartphones. While smartphones do many jobs well, the primary job to be done could be described as “Communicate with others and help me speed up daily tasks while on the go.” For some users, doing this job well means just having the ability to run a limited set of functions such as phone calls, text messages, email, music and web browsing. These are basic needs that would satisfy the lower-end segment needs. For other users, doing this job well means having a gorgeous screen to look at, powerful speakers to play music out loud with and advanced security features to make it easy and convenient to authenticate you as the rightful user. These are sophisticated needs that satisfy the high end of the market.

Over time, the needs of people in a market will inflate gradually and what people used to think was novel and unique will eventually become expected across the board. With smartphones, this has happened already with screen size. In 2007, when Apple launched the iPhone (arguably the world’s first true smartphone), the screen was 3.5″. Other smartphones that came out were around that size as well. Several years later Samsung introduced the Galaxy Note with a 5.3″ screen size. Over time the entire market began to prefer screen sizes of at least 4.5″-5″ or larger.

To keep pace with these most demanding customers, companies create sustaining innovations to meet their needs. The goal of an existing provider in a market is to sustain their current business model and meet the needs of the most demanding customers who are willing to pay a premium for the added performance.

In the iPhone’s case, lately Apple has been very aggressive about pushing the market into higher and higher performance (and prices). The risk they run is in alienating the average or low-end user base with products that are overkill and too expensive for their desires.

That said, Apple is usually happy to cede the lower third/half of a market to other providers. Steve Jobs once famously said

“We don’t know how to build a sub-$500 computer that is not a piece of junk.” – Steve Jobs

Despite their focus on premium products, for the last several years Apple has worked hard to create numerous sustaining innovations in order to establish a broad lineup of smartphones that can meet the needs of everyone in that upper half of users. They do this primarily through creating new models with better features and price reductions on their prior year models. Note that at Apple’s September 2018 iPhone presentation, they showed a lineup that ranged from $449 for the iPhone 7 (a $100 price reduction from 2017) to a new phone, the XS Max, at a new high price of $1099. This distribution is intended to give Apple complete coverage of the upper half of the market – allowing other providers such as Motorola which sells smartphones ranging from $125 for the Moto E to $400 for the Moto Z to meet the needs of the lower half of the market.

To understand a market, and consequently the implications of various innovation strategies, it helps to map it out in terms of solutions offered for a job to be done and the price of those solutions. I call this a market map. In the image below I’ve created a market map for the smartphone market but limited the products shown to just Apple, Motorola, BLU and Lamborghini to make it simple. While Apple and Motorola’s phones illustrate the breadth of the market, every market always has low outliers and high outliers and it can be helpful to list those as points of reference for the extreme upper and lower bounds of the market. In this case, BLU with it’s $50 smartphone is considered a low outlier with likely relatively low volume and Lamborghini with it’s $6000 smartphone labeled a high outlier with almost certainly very low volume.

Critics have said that by creating all these different phone options (e.g. sustaining innovations), Apple is betraying the values of simplicity and focus that Steve Jobs so adamantly stood for. While there may be some truth to that, Apple is also clearly doing extensive sustaining innovation with the iPhone in order to not just grow but also to maintain their market leadership position.

Remember, for sustaining innovations the objective is to sustain the existing business model and meet the needs of the most demanding customers who are willing to pay a premium. By those terms, Apple is doing a very good job with their sustaining innovation strategy. The only risk to it that they must guard against is overshooting customer needs and going too premium too fast.

That’s when a prime opportunity for disruptive innovation opens up.

Innovation Type 2: Disruptive Innovations – A Low Cost Alternative Enabled By New Technology

During the 1980’s and 1990’s, large corporations that failed because someone else out-innovated them were usually blamed as having incompetent managers. In his seminal work, The Innovator’s Dilemma, Clayton Christensen defied that common storyline by positing that these big company managers were making very rational and shrewd decisions (such as investments in sustaining innovation) given their market position and the requests of customers.

That said, the risk they run is in going too premium, too fast and thus creating an opportunity in the market for someone else to provide a more focused, lower cost solution that appeals to the basic need segments in the market.

This window of opportunity presents itself when the following conditions are met:

- The market leader keeps releasing higher and higher priced products and services that only appeal to the premium segment of the market

- Since the latest solutions only appeal the high end of the market, the lower end need customers are cajoled into paying more than they otherwise would because they are effectively forced into buying more than they need

- A new technology comes along that enables a dramatically (usually ~10X) lower cost and more focused solution that, while still not appealing to the higher end of the market, appeals to the lower end because it’s price is much lower and it does only what they need it to do

I like to refer to these new technologies as technology runways which are platforms on which new solutions are created and improved over time. The image below provides some examples of technology runways.

While there are countless good examples of disruptive innovation (so many that Clayton Christensen’s theory is basically accepted as a law of technology markets), I’ll illustrate my favorite example: Chromebooks.

By 2010 Microsoft and the classic PC architecture was pretty much the only game in town if you wanted to buy a laptop. Netbooks had been around a while with limited success and iPads had just barely launched but for most mainstream laptop PC customers you only had one choice: a Microsoft Windows powered PC laptop that ranged in price from $800-1500. Or if you really wanted to splurge, you could buy an Apple Macbook Pro but that was even more expensive.

For many laptop buyers, especially among the older segments, their only use case was limited to browsing the internet and checking email. But Microsoft PC’s offered so much more! They could run all sorts of apps, everything from Adobe design applications to gaming and everything in between. The image below illustrates the opening in the market for a disruptive innovation to come along.

Around the same time, roughly 2010, cloud computing, the ability to leverage server capabilities to perform heavy computing tasks over a high-speed internet connection, was just starting to gain it’s stride. With that technology, Google thought of an opportunity: create a free operating system focused solely around one app – their popular Chrome browser. The major advantage to this would be since the OS was essentially one app, the computer hardware needed to run it was inexpensive. They partnered with OEM’s who were able to create Chromebooks for roughly 5-10X less expensive than a regular PC laptop – landing at around $150-400 in price.

In the beginning Chromebooks didn’t sell very well. Many people, including then Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer, initially scoffed at it. For rational reasons too – it was underpowered, unproven in the market and ultimately seemed too low-end to appeal to the PC laptop market.

Yet, as noted in the graphic above, Chromebooks gobbled up market share at an incredible pace. Starting out at less than 1% in 2012 and just 5 years later achieving market dominance with 58%.

The error most big company executives make when evaluating threats such as the Chromebook is the exact error Steve Ballmer made – thinking it’s not going to appeal to people because it can’t do half of what their flagship products can do. That’s just the point of a disruptive innovation – leverage a new technology runway (e.g. cloud computing), do one thing very well (web browsing) and ignore all the other functionality of the premium competitors.

Google’s entry into the PC operating system market has now forced Microsoft to focus on the premium segment of the market where their current Surface line is aimed.

Innovation Type 3: New Market Innovations – Modifying Existing Solutions For New Markets

Another important type of innovation that companies have deployed is one in which they take an existing solution and modify and sell it for use in a different market. The goal of a new market innovation is to target non consumers and expand their existing market.

One could argue that Google did this with Chrome OS. Not only was it a disruptive innovation in leveraging new technology and creating a more focused solution that was much lower cost, they also modified the Chrome browser to be a light OS and targeted non-consumers, in this case the OEM market, by offering it for free.

Another example I like to use is Arm and Hammer baking soda. Baking soda was traditionally used for baking but when its other uses became compelling, Arm and Hammer modified their packaging to inform consumers that it also can be used for cleaning, laundry and deodorizing.

New market innovations are relatively straightforward to understand and apply but there are two key considerations if you’re going to attempt a new market innovation. The first is understand the new market segments and the second is clearly understand your competition in that new market.

For example, when Arm and Hammer modified its packaging to showcase their baking soda as great for cleaning, laundry and deodorizing, the customer who was looking for baking soda in the store is likely going to think the following…

“I already use Comet for cleaning, is baking soda really a better value than me using Comet?”

Or “I use Tide as a laundry detergent, is baking soda really a better value than Tide?”

Or “I use Febreeze for deodorizing, is baking soda more effective than Febreeze?”

These scenarios pose a handful of challenges for Arm and Hammer in their attempt to penetrate those markets. The first is, how will they reach people beyond just the ones who were seeking out baking soda in the first place? This is a product positioning challenge and may require them to create a dedicated product branded for each use case so they can reach the people who are seeking out cleaning solutions – not just reaching the people who want baking soda and hoping they may also have a need for cleaning solutions.

The second challenge is, even if you do solve the first problem of reaching those who are focused on each use case, how will you position the product to compete well against the incumbent leaders of the new market? In this case, how will you position a baking soda based cleaner against powerhouses such as Comet and Lysol? Or against Tide and Gain in laundry?

The answer is that for new market innovations to be successful, like the Chrome OS example, it helps to have a disruptive value proposition that is ~5-10X better than the incumbent leader. For example, if Arm and Hammer could clearly demonstrate their baking soda was just as good as Tide but 5-10X lower price, that new market innovation has a strong chance of success.

Then The iPhone Changes Everything

In 2007 the world was very different. Most computers ran windows, most high-end phones were called PDA’s (Personal Digital Assistant) and the theory of disruptive innovation alone was a good theory that seemed to describe the vast majority of successful innovations that were discussed at the time.

Then the very first iPhone came along.

It’s well-documented that Clayton Christensen blew it with his theory of disruptive innovation in predicting the market failure of the iPhone. Some commentators even thought this invalidated the theory in general.

Like Christensen, Steve Ballmer of Microsoft also scoffed at the iPhone’s chances for success due to it’s high price and lack of a physical keyboard.

After the iPhone experienced wild success, Christensen modified the application of his theory to describe the iPhone as disruptive to laptop computers in general. Which is true, but less effective as a clear predictive model for innovation success if the theory must be applied in non-intuitive ways like that – otherwise Christensen would have made the right prediction from the beginning!

Despite the imperfections of the theory and the naysayers, the theory of disruptive innovation has been validated countless times in countless industries. But why then was the iPhone different? How did the iPhone succeed when it clearly defies the logic of arguably the most consequential management theory of the last 50 years?

The short answer is, the iPhone was an anomaly.

In Christensen’s book “Seeing What’s Next” he described a model for creating theories in general that is outlined below. Essentially the process consists of observations which are then categorized which can then be generalized into a predictive theory of cause and effect. For every new observation (such as a new product that comes to market), the theory predicts an eventual outcome and that product either ends up confirming the theory or is an anomaly. In the case of Chromebooks, the theory is confirmed. In the case of iPhone, the theory was not confirmed and the iPhone is considered an anomaly.

When Jobs announced the iPhone in January 2007, he started the meeting by saying that he was going to announce 3 exciting new products: an iPod, a phone and an internet communicator.

To position the iPhone against the competition, Jobs used this slide:

This introduction is important because it clearly conveys the value of the iPhone in terms of two things:

- The combined functionality of an iPod, phone and internet communicator

- Ease of use

By combining the power of a small computer with a user interface that was easy enough for a child to use, Apple was able to create a game-changing device.

So where did the theory of disruptive innovation break down with regards to the iPhone?

It has everything to do with the fact that the iPhone was not just “a better phone” as Christensen assumed. Rather, as discussed earlier, it is three devices integrated into one:

- An iPod

- A phone

- An internet communicator

Having three devices integrated into one is a vastly different strategy than classical “disruptive innovation” but it can still succeed and the reason is because multiple jobs to be done have now been combined into one solution and the cumulative value (or price) of getting those jobs done is combined as well. Steve Jobs knew this perfectly well and he explained it while walking people through how Apple was going to price the first iPhone. Below is a screenshot of this part of the announcement…

Jobs used the price of an iPod and the price of a Blackberry on a 2-year contract to determine the total price of the iPhone at $499 on a 2-year contract

Below is another screenshot from that part of the announcement…

Jobs used this image to show that iPhone provided so many more benefits than just combining an iPod and a Blackberry into one. Ultimately he built a compelling value proposition.

His thought process was as follows:

A 4GB iPod = $199 price

A Blackberry = $299 price on a 2-year contract

The 4GB iPhone = $499 price on a 2-year contract and consumers get to have a host of other benefits such as video, widescreen, multi-touch, Wi-Fi, Safari browser, HTML email, Cover Flow, visual voice mail, and more all for no added premium.

As shown in an earlier graph, Apple went on to sell millions of iPhones and now the product represents the bulk of Apple’s revenues. The bottom line takeaway is that if you want to create a breakthrough innovation, one way to do it is to combine the functionality of multiple products into one in a way that is simple and easy to use. This is exactly what the iPhone did and because of it, Apple was able to charge dearly for the device and make incredible margins. Keep in mind that the $499 price is a subsidized 2-year contract price from AT&T!

All these conditions and results combine to prompt a new theory of innovation…

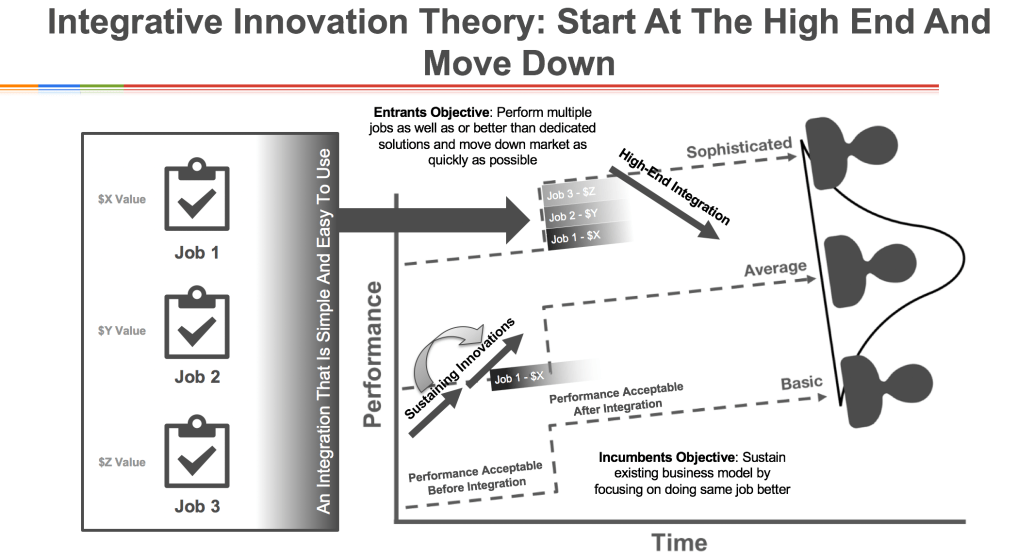

Innovation Type 4: Integrative Innovation – Multiple Jobs to Be Done In One Elegant Solution

The main thesis of “Integrative Innovation” is the idea that a market’s ability to adopt more performance and absorb higher prices will increase according to the number and value of jobs to be done that have been integrated into one device in a way that is simple and easy to use. Christensen’s theory of disruptive innovation assumes that in order to be disruptive, products must focus on one job to be done, start at the low-end, improve performance over time and eventually become good enough to capture a large portion of the market. Integrative innovation is the opposite of that. Instead of starting out as not good enough and moving up in performance and cost, Integrative Innovation is about combining multiple jobs into one and creating a very high-performance/high-cost solution to begin with and quickly moving down in cost to capture large portions of the market.

As the above graphic illustrates, the iPhone fits this theory well. In September 2007, just a few months after launch, Apple reduced the price of the iPhone substantially and within a few years even developed a lower-cost model called the 5C.

As a general model, the theory of integrative innovation is represented below.

This also explains, to a large extent, the progression of iPods. The iPod started out with high capacity and a large screen but as time went on Apple introduced smaller, less-expensive models and eventually the iPod Nano became the most popular iPod sold.

The good part about Integrative Innovation and Disruptive Innovation is that they can co-exist by simply representing two opposing types of game-changing innovations. I am still a firm believer in disruptive innovation theory but it clearly falls short in explaining the iPhone – one of the most important innovations of our time.

Another good example of integrative innovation is Tesla. In 2006, a couple years before the first production Tesla Roadster launched, Elon Musk wrote a blog post called “The Secret Tesla Motors Master Plan“. In it he described his plan for Tesla as follows:

“The strategy of Tesla is to enter at the high end of the market, where customers are prepared to pay a premium, and then drive down market as fast as possible to higher unit volume and lower prices with each successive model.” – Elon Musk, 2006 Tesla Blog Post

Like Musk says in the post, the Roadster is not a mass market vehicle but it gets his foot in the door to start creating what he ultimately wants to build – a high-performance electric car for the mass market. As such, the Roadster almost falls into the high outlier category while the true first integrative innovation that Tesla built was the Model S. The image below is how I interpret his blog post and Tesla’s progression:

Conclusion

In summary, I’ve prepared the following cheat sheet as a way to visualize how the four types of innovation relate to each other in terms of technology and commercialization. I’ve also made this cheat sheet available as a free downloadable pdf you can get by clicking here. Get Your Free Cheat Sheet!

For more information on how to apply the four types of innovation to your business, be sure to sign up for my free three-part video series on innovation available here.